Thomas of Celano - Dies Irae

Older Recording, Excerpt

Newer Recording, Complete

Thomas of Celano (Italian: Tommaso da Celano; c. 1200 – c. 1260-1270) was an Italian friar of the Franciscans (Order of Friars Minor), a poet, and the author of three hagiographies about Saint Francis of Assisi.

Thomas was from Celano in Abruzzo. The first of his works on Francis was Vita prima ("First Life"), a work on the saint's early life, commissioned by Pope Gregory XI in 1228 at the time Francis's canonization. The second work, Vita secunda ("Second Life") was commissioned by Crescentius of Jessi, the Minister General of the Franciscan Order sometime between 1244 and 1247, and reflects changing official perspectives on Francis in the decades after his death. The third is a treatise on the saint's miracles, written sometime between around 1254 and 1257 at the bidding of Blessed John of Parma, who succeeded Crescentius as Minister General.

Thomas's authorship of the three works on Francis of Assisi is well-established. Thomas also wrote Fregit victor virtualis and Sanctitatis nova signa in honor of Francis. Life of St. Clare of Assisi, on the early life of Saint Clare of Assisi and the hymn Dies Irae are also traditionally attributed to him, but the authorship of both works is in fact uncertain.

Thomas was not among the very earliest disciples of Francis, but he joined the Franciscans around 1215, during the saint's lifetime, and evidently knew him personally. In 1221, Thomas was sent to Germany with Caesarius of Speyer to promote the new order there, and in 1223 was named "sole guardian" (custos unicus) of the order's Rhineland province, which included convents at Cologne, Mainz, Worms, and Speyer. Within a few years he was back in Italy, where he seems to have remained for the rest of his life, with some possible short-term missions to Germany. In 1260 he settled down to his last post, as spiritual director to a convent of Clarisses in Tagliacozzo, where he died some time between 1260 and 1270. He was at first buried in the church of S. Giovanni Val dei Varri, attached to his monastery, but his body is now reburied in the church of S. Francesco at Tagliacozzo.

***

[Michelangelo (1475-1564) - The Last Judgment]

Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) is a famous 13th-century Latin hymn thought to be written by Thomas of Celano. It is a medieval Latin poem, differing from classical Latin by its accentual (non-quantitative) stress and its rhymed lines. The meter is trochaic. The poem describes the day of judgment, the last trumpet summoning souls before the throne of God, where the saved will be delivered and the unsaved cast into eternal flames. The hymn is used as a sequence in the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass in the extraordinary form (1962 missal). It is not used in the ordinary form (1970) of the Roman Missal.

Those familiar with musical settings of the Requiem Mass—such as those by Mozart or Verdi—will be aware of the important place of the Dies Iræ in the liturgy. Nevertheless it fell foul of the preferences of the "Consilium for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Liturgy"—the Vatican body charged with implementing (and indeed drafting) the reforms to the Catholic Liturgy ordered by the Second Vatican Council. The architect of these reforms, Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, explains the mind of the members of the Consilium:

They got rid of texts that smacked of a negative spirituality inherited from the Middle Ages. Thus they removed such familiar and even beloved texts as the Libera me, Domine, the Dies Iræ, and others that overemphasized judgment, fear, and despair. These they replaced with texts urging Christian hope and arguably giving more effective expression to faith in the resurrection.

It remained as the sequence for the Requiem Mass in the Roman Missal of 1962 (the last edition before the Second Vatican Council) and so is still heard in churches where the Tridentine Latin liturgy is celebrated.

The "Dies Irae" is still suggested in the Liturgy of the Hours for the Office of the Dead and during last week before Advent as the opening hymn for the Office of Readings, Lauds and Vespers (divided into three parts).

The Latin text is taken from the Requiem Mass in the 1962 Roman Missal. The English version below was translated by William Josiah Irons in 1849 and appears in the English Missal. Note that the below translation is not literal, but modified to fit the rhyme and meter.

1

Dies iræ! dies illa

Solvet sæclum in favilla

Teste David cum Sibylla!

2

Quantus tremor est futurus,

quando judex est venturus,

cuncta stricte discussurus!

3

Tuba mirum spargens sonum

per sepulchra regionum,

coget omnes ante thronum.

4

Mors stupebit et natura,

cum resurget creatura,

judicanti responsura.

5

Liber scriptus proferetur,

in quo totum continetur,

unde mundus judicetur.

6

Judex ergo cum sedebit,

quidquid latet apparebit:

nil inultum remanebit.

7

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus?

Quem patronum rogaturus,

cum vix justus sit securus?

8

Rex tremendæ majestatis,

qui salvandos salvas gratis,

salva me, fons pietatis.

9

Recordare, Jesu pie,

quod sum causa tuæ viæ:

ne me perdas illa die.

10

Quærens me, sedisti lassus:

redemisti Crucem passus:

tantus labor non sit cassus.

11

Juste judex ultionis,

donum fac remissionis

ante diem rationis.

12

Ingemisco, tamquam reus:

culpa rubet vultus meus:

supplicanti parce, Deus.

13

Qui Mariam absolvisti,

et latronem exaudisti,

mihi quoque spem dedisti.

14

Preces meæ non sunt dignæ:

sed tu bonus fac benigne,

ne perenni cremer igne.

15

Inter oves locum præsta,

et ab hædis me sequestra,

statuens in parte dextra.

16

Confutatis maledictis,

flammis acribus addictis:

voca me cum benedictis.

17

Oro supplex et acclinis,

cor contritum quasi cinis:

gere curam mei finis.

1

Day of wrath! O day of mourning!

See fulfilled the prophets' warning,

Heaven and earth in ashes burning!

2

Oh what fear man's bosom rendeth,

when from heaven the Judge descendeth,

on whose sentence all dependeth.

3

Wondrous sound the trumpet flingeth;

through earth's sepulchers it ringeth;

all before the throne it bringeth.

4

Death is struck, and nature quaking,

all creation is awaking,

to its Judge an answer making.

5

Lo! the book, exactly worded,

wherein all hath been recorded:

thence shall judgment be awarded.

6

When the Judge his seat attaineth,

and each hidden deed arraigneth,

nothing unavenged remaineth.

7

What shall I, frail man, be pleading?

Who for me be interceding,

when the just are mercy needing?

8

King of Majesty tremendous,

who dost free salvation send us,

Fount of pity, then befriend us!

9

Think, good Jesus, my salvation

cost thy wondrous Incarnation;

leave me not to reprobation!

10

Faint and weary, thou hast sought me,

on the cross of suffering bought me.

shall such grace be vainly brought me?

11

Righteous Judge! for sin's pollution

grant thy gift of absolution,

ere the day of retribution.

12

Guilty, now I pour my moaning,

all my shame with anguish owning;

spare, O God, thy suppliant groaning!

13

Thou the sinful woman savedst;

thou the dying thief forgavest;

and to me a hope vouchsafest.

14

Worthless are my prayers and sighing,

yet, good Lord, in grace complying,

rescue me from fires undying!

15

With thy favored sheep O place me;

nor among the goats abase me;

but to thy right hand upraise me.

16

While the wicked are confounded,

doomed to flames of woe unbounded

call me with thy saints surrounded.

17

Low I kneel, with heart submission,

see, like ashes, my contrition;

help me in my last condition.

The poem appears complete as it stands at this point. Some scholars question whether the remainder is an addition made in order to suit the great poem for liturgical use, for the last stanzas discard the consistent scheme of triple rhymes in favor of rhymed couplets, while the last two lines abandon rhyme for assonance and are, moreover, catalectic: (this information is questionable. Editors at this point have actually offered this piece at a genuine requiem - it is sung, it is true, it is appropriate... Dona eis requiem.)

18

Lacrimosa dies illa,

qua resurget ex favilla

judicandus homo reus.

Huic ergo parce, Deus:

19

Pie Jesu Domine,

dona eis requiem. Amen.

18

Ah! that day of tears and mourning!

From the dust of earth returning

man for judgment must prepare him;

Spare, O God, in mercy spare him!

19

Lord, all pitying, Jesus blest,

grant them thine eternal rest. Amen.

In 1970 the Dies Iræ was removed from the Missal and since 1971 it is proposed ad libitum as a hymn for the Liturgy of the Hours at the Office of Readings, Lauds and Vespers. For this purpose stanza 19 was deleted and the poem divided into three sections: 1-6 (for the Office of Readings), 7-12 (for Lauds) and 13-18 (for Vespers. In addition Qui Mariam absolvisti in stanza 13 was replaced by Peccatricem qui solvisti so that that line would now mean, "You who freed the sinful woman." In addition a doxology is given after stanzas 6, 12 and 18

doxology:

O tu, Deus majestatis,

alme candor Trinitatis

nos coniunge cum beatis. Amen.

doxology:

O God of majesty

nourishing light of the Trinity

join us with the blessed. Amen.

A major inspiration of the hymn seems to have come from the Vulgate translation of Zephaniah 1:15–16:

Dies iræ, dies illa, dies tribulationis et angustiæ, dies calamitatis et miseriæ, dies tenebrarum et caliginis, dies nebulæ et turbinis, dies tubæ et clangoris super civitates munitas et super angulos excelsos.

That day is a day of wrath, a day of tribulation and distress, a day of calamity and misery, a day of darkness and obscurity, a day of clouds and whirlwinds, a day of the trumpet and alarm against the fenced cities, and against the high bulwarks. (Douai Bible)

Other images come from Revelation 20:11–15 (the book from which the world will be judged), Matthew 25:31–46 (sheep and goats, right hand, contrast between the blessed and the accursed doomed to flames), 1 Thessalonians 4:16 (trumpet), 2 Peter 3:7 (heaven and earth burnt by fire), Luke 21:26–27 ("men fainting with fear ... they will see the Son of Man coming"), etc.

From the Jewish liturgy, the prayer Unetanneh Tokef also appears to have been a source: "We shall ascribe holiness to this day, For it is awesome and terrible"; "the great trumpet is sounded", etc.

A number of English translations of the poem have been written and proposed for liturgical use. A Franciscan version can be read here. A very loose Protestant version was made by John Newton; it opens:

Day of judgment! Day of wonders!

Hark! the trumpet's awful sound,

Louder than a thousand thunders,

Shakes the vast creation round!

How the summons wilt the sinner's heart confound!

Jan Kasprowicz, a Polish poet, wrote a hymn entitled Dies irae which describes the Judgement day. The first six lines (two stanzas) follow the original hymn's meter and rhyme structure, and the first stanza translates to "The trumpet will cast a wondrous sound."

The American writer Ambrose Bierce published a satiric version of the poem in his 1903 book Shapes of Clay, preserving the original metre but using humorous and sardonic language; for example, the second verse is rendered:

Ah! what terror shall be shaping

When the Judge the truth's undraping -

Cats from every bag escaping!

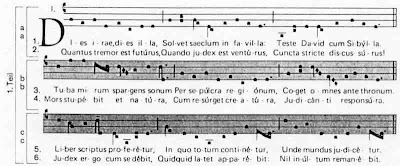

The hymn music, with the words of the first stanza, is provided here:

The words have often been set to music as part of the Requiem service, originally as a sombre plainchant. It also formed part of the traditional Catholic liturgy of All Souls Day. Music for the Requiem mass has been composed by many composers, including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Hector Berlioz, Giuseppe Verdi and Hector Berlioz.

The traditional Gregorian melody has also been quoted in a number of other classical compositions, among them:

Thomas Adès Living Toys

Mark Alburger Aerial Requiem, Street Songs, Diabolical Variations

Charles-Valentin Alkan Symphony for Solo Piano, Souvenirs Trois Morceaux dans le genre pathetique, Op. 15 - Morte

Hector Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique

Andrew Boysen Grant Them Eternal Rest (throughout)

Johannes Brahms Klavierstück op. 118/6

Benjamin Britten War Requiem

Antoine Brumel Dies Irae

Iva Boulanger Funerailles du Soldat

Elliott Carter In Sleep, In Thunder, #4

Marc-Antoine Charpentier Grand Office des Morts

George Crumb Black Angels, Makrokosmos Volume II, Star Child

Luigi Dallapiccola Luigi Canti Di Prigiona

Michael Daugherty Metropolis Symphony 4th mvmt, “Red Cape Tango”. Dead Elvis

Ernő Dohnányi Eb minor Piano Rhapsody, Op. 11, No. 4

Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, mvmt 1

Martin Ellerby Paris Sketches, mvmt 3

Antonio Estevez - La Cantata Criolla

Jean Françaix Cinq poemes de Charles d'Orléans

Diamanda Galás Masque Of The Red Death: Part I - Divine Punishment & Saint Of The Pit:

Track 5. Heautontimorounenos (Restless Souls)

Roberto Gerhard Piano Concerto

Alexander Glazunov Moyen Age

Leopold Godowsky Piano Sonata in E Minor, mvmt 5

Berthold Goldschmidt Beatrice Cenci opera

Charles Gounod Faust Opera, Act IV

Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 103, "The Drumroll"

Vagn Holmboe Symphony #10, 1st & 4th mvmts, Symphony #11, 1st mvmt

Arthur Honegger La Danse des Morts

Gottfried Huppertz Score for Metropolis

Karl Jenkins Requiem

Miloslav Kabeláč Symphony No. 8 Antiphonies

Aram Khachaturian Symphony #2 The Bell Symphony, Spartak

Krzysztof Kicior Visions Reflexives

György Ligeti Le Grand Macabre

Franz Liszt Dante Symphony, Totentanz

Charles Martin Loeffler One Who Fell in Battle, Rhapsodies for oboe, viola, and piano, 1st movement, and several songs

Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2, mvmt 1, 3, and 5

Bohuslav Martinu Concerto for Cello and Orchestra No. 2, final movement.

Nikolai Medtner Piano Quintet in C Major, Op. Posthumous

Nikolai Myaskovsky Piano Sonata #2, Symphony #6

Modest Mussorgsky Night on Bald Mountain, Songs and Dances of Death

Carl Orff Carmina Burana

Krzysztof Penderecki Dies Irae

Jubilaeum Super Mutationes op. 50 ????

Ildebrando Pizzetti Requiem, Assassinio nella cattedrale

Sergei Rachmaninoff Études-Tableaux, Op. 39, No. 2, Isle of the Dead, Prelude in e minor, Op. 32 #4, Piano Sonata no.1 in d minor Op. 28, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphonic Dances, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Symphony No. 3, The Bells

Ottorino Respighi Brazilian Impressions

Marcel Rubin Symphony #4, 2nd mvmt (Dies Irae)

Camille Saint-Saëns Danse Macabre, Requiem, Symphony No. 3 ("Organ Symphony")

Aulis Sallinen Aulis Dies Irae, Op. 47

Juelz Santana The Second Coming

Ernest Schelling Impressions from an Artist's Life

Peter Schickele Unbegun Symphony

William Schmidt - Tuba mirum

Alfred Schnittke Symphony #1, mvmt 4

Dmitri Shostakovich Music for Hamlet, Symphony No. 14

Jean Sibelius Lemminkäinen Suite

Stephen Sondheim Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street "The Ballad of Sweeney Todd"

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, Cyclic Sequence on Dies Irae (from Mass), Variations and Triple Fugue on Dies Irae

Ronald Stevenson Passacaglia on DSCH (1962-3)

Richard Strauss Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Dance of the Seven Veils from Salome

Igor Stravinsky The Rite of Spring (sacrifice intro); Three pieces for String Quartet (III, "Canticle"); L'Histoire du Soldat

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Grand Sonata, Op. 37; Manfred Symphony; Modern Greek Song, Op. 16 #6; Marche Funebre, Op. 21, #4, Suite No. 3 Op. 55

Frank Ticheli Vesuvius

Ralph Vaughan Williams, Five Tudor Portraits

Adrian Williams Dies Irae

James Yannatos Trinity Mass

Eugène Ysaÿe Sonata in A minor, Op. 27, No. 2 (Obsession)

Dan Cavanagh A Time of Reckoning

Raymond Deane Seachanges

The tune is parodied in the main theme of the movie It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

The musical Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street contains several variations of the Dies Irae throughout its score, most notably in the recurrent "Ballad of Sweeney Todd," and as part of the underscoring in the climactic "Epiphany".

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used the first, the sixth and the seventh stanza of the hymn in the scene "Cathedral" in the first part of his drama Faust (1808).

Oscar Wilde composed a Sonnet on Hearing the Dies Irae Sung in the Sistine Chapel, contrasting the "terrors of red flame and thundering" depicted in the hymn with images of "life and love".

Ambrose Bierce wrote a poem titled A day of wrath which, while following the structure of the hymn, gives a very free interpretation of it

T. S. Eliot used Dies Irae in the final part of Murder in the Cathedral (1935) just before the assassination of Archbishop Thomas Becket. It is to be sung in Latin by a distant choir.

Kurt Vonnegut wrote Stones, Time, & Elements - A Humanist Requiem in opposition to the classical Requiem and in particular to the "Dies Irae," which he found "vengeful and sadistic" (and mistakenly reputed a "piece of poetry by committee from the Council of Trent"). His Requiem was set to music by Edgar David Grana.

Jonathon Larson used the first four words of Dies Irae in the song "La Vie Boheme," from the musical RENT, spoken by philosophy scholar Tom Collins and songwriter Roger Davis.

Anne Rice used the first stanza and first line of the second stanza in her novel, The Vampire Armand (1998), with a slightly different translation than given above.

The 19th stanza (except for the word 'Amen') is used in two parts of Monty Python and the Holy Grail: the Burn-the-Witch and Holy Hand Grenade scenes.

***

The Requiem (from Latin requiem, accusative case of requies, rest) or Requiem Mass (informally, a funeral Mass), also known formally (in Latin) as the Missa pro defunctis or Missa defunctorum, is a liturgical service of the Roman Catholic Church, Anglo-Catholic Anglicans, as well as certain Lutheran Churches in the United States. There is also a requiem, with a wholly different ritual form and texts, that is observed in the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches. The common theme of requiems is prayer for the salvation of the soul(s) of the departed, and it is used both at services immediately preceding a burial, and on occasions of more general remembrance.

Requiem is also the title of various musical compositions used in such liturgical services or as concert pieces as settings of the portions of that Mass which have been traditionally sung in the Roman Catholic liturgy.

While the prayers in the regular Mass as the Introit and Gradual change according to the Calendar of Saints, the text for the requiem Mass is particularly fixed. Originally such funeral musical compositions were meant to be performed in liturgical service, with monophonic chant. Eventually the dramatic character began to appeal to composers to an extent that made the requiem a genre of its own.

This use of the word requiem comes from the opening words of the Introit: Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis. (Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them.) The requiem form of the Tridentine Mass differs from the ordinary Mass in omitting certain joyful passages such as the Alleluia, in never having the Gloria or the Credo, in adding the sequence Dies Iræ, in altering the Agnus Dei, in replacing "Ite missa est" with "Requiescant in pace", and in omitting the final blessing. These distinctions have not been kept in the Roman Rite as revised after the Second Vatican Council.

The regular texts of the musical portions to be found in the Roman Catholic liturgy are the following:

Introit:

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis. Te decet hymnus Deus, in Sion, et tibi reddetur votum in Ierusalem. Exaudi orationem meam; ad te omnis caro veniet. Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis.

(“Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them. A hymn becomes you, O God, in Zion, and to you shall a vow be repaid in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer; to you shall all flesh come. Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them.”)

Kyrie eleison, as the Kyrie the Ordinary of the Mass:

Kyrie eleison; Christe eleison; Kyrie eleison

This is Greek for “Lord have mercy; Christ have mercy; Lord have mercy.” Traditionally, each utterance is sung three times.

Gradual:

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine; In memoria æterna erit justus, ab auditione mala non timebit.

(“Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord. He shall be justified in everlasting memory, and shall not fear evil reports.”)

Tract:

Absolve, Domine, animas omnium fidelium defunctorum ab omno vinculo delictorum et gratia tua illis succurente mereantur evadere iudicium ultionis, et lucis æterne beatitudine perfrui.

(“Forgive, O Lord, the souls of all the faithful departed from all the chains of their sins and may they deserve to avoid the judgment of revenge by your fostering grace, and enjoy the everlasting blessedness of light.”)

Sequence:

Dies iræ, dies illa

Solvet sæclum in favilla,

teste David cum Sibylla...

(“Day of wrath, a day that the world will dissolve in ashes, as foretold by David and the Sibyl...”) (See above for full text)

Offertory:

Domine, Jesu Christe, Rex gloriæ, libera animas omnium fidelium defunctorum de pœnis inferni et de profundo lacu. Libera eas de ore leonis, ne absorbeat eas tartarus, ne cadant in obscurum; sed signifer sanctus Michæl repræsentet eas in lucem sanctam, quam olim Abrahæ promisisti et semini ejus.

(“Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, free the souls of all the faithful departed from infernal punishment and the deep pit. Free them from the mouth of the lion; do not let Tartarus swallow them, nor let them fall into darkness; but may the sign-bearer, Saint Michael, lead them into the holy light which you promised to Abraham and his seed.”)

Hostias et preces tibi, Domine, laudis offerimus; tu suscipe pro animabus illis, quarum hodie memoriam facimus. Fac eas, Domine, de morte transire ad vitam. Quam olim Abrahæ promisisti et semini ejus.

(“O Lord, we offer you sacrifices and prayers in praise; accept them on behalf of the souls whom we remember today. Make them pass over from death to life, as you promised to Abraham and his seed.”)

Sanctus, as the Sanctus prayer in the Ordinary of the Mass:

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus, Dominus Deus Sabaoth; pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua.

(“Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Hosts; Heaven and earth are full of your glory”).

Hosanna in excelsis.

(“Hosanna in the highest”).

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.

(“Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord”).

Hosanna in excelsis. (reprise)

Agnus Dei, text as the Agnus Dei in the Ordinary of the Mass, but with the petitions miserere nobis changed to dona eis requiem, and dona nobis pacem to dona eis requiem sempiternam:

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem,

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem,

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem sempiternam.

(“Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, grant them rest, … grant them rest eternal.”).

Communion:

Lux æterna luceat eis, Domine, cum sanctis tuis in æternum, quia pius es. Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine; et lux perpetua luceat eis.

(“May everlasting light shine upon them, O Lord, with your saints forever, for you are faithful. Grant them eternal rest, O Lord, and may everlasting light shine upon them.”)

As with the regular Sunday or ferial Mass in penitential seasons, the Gloria (from the Ordinary) is always omitted in a Requiem Mass. In the Tridentine form of the Roman Rite and Alleluia (from the Proper) is also omitted, as being overly joyful, and is replaced by the Tract. Likewise, the Credo (which, like the Gloria, is used in the ordinary Mass only on more solemn feasts) is never used in the Requiem Mass. The Dies iræ was rendered optional in 1967 and was omitted altogether from the revised Mass in 1969; at the same time, the Tract was abolished and the Alleluia added to the Requiem Mass, except in Lent, when it is replaced also at ordinary Masses by a less joyful acclamation.

For many centuries the texts of the requiem were sung to Gregorian melodies. The Requiem by Johannes Ockeghem, written sometime in the latter half of the 15th century, is the earliest surviving polyphonic setting. There was a setting by the elder composer Dufay, possibly earlier, which is now lost: Ockeghem's may have been modelled on it.

Many early requiems employ different texts that were in use in different liturgies around Europe before the Council of Trent set down the texts given above. The requiem of Brumel, circa 1500, is the first to include the Dies Iræ. In the early polyphonic settings of the Requiem, there is considerable textural contrast within the compositions themselves: simple chordal or fauxbourdon-like passages are contrasted with other sections of contrapuntal complexity, such as in the Offertory of Ockeghem's Requiem.

In the 16th century, more and more composers set the Requiem mass. In contrast to practice in setting the Mass Ordinary, many of these settings used a cantus-firmus technique, something which had become quite archaic by mid-century. In addition, these settings used less textural contrast than the early settings by Ockeghem and Brumel, although the vocal scoring was often richer, for example in the six-voice Requiem by Jean Richafort which he wrote for the death of Josquin des Prez.

Other composers who wrote Requiems before 1550 include Pedro de Escobar, Antoine de Févin, Cristóbal Morales, and Pierre de La Rue; that by La Rue is probably the second oldest, after Ockeghem's.

Over 2,000 requiems have been composed to the present day. Typically the Renaissance settings, especially those not written on the Iberian Peninsula, may be performed a cappella (i.e. without necessary accompanying instrumental parts), whereas beginning around 1600 composers more often preferred to use instruments to accompany a choir, and also include vocal soloists. There is great variation between compositions in how much of liturgical text is set to music.

Most composers omit sections of the liturgical prescription, most frequently the Gradual and the Tract. Fauré omits the Dies Iræ, while the very same text had often been set by French composers in previous centuries as a stand-alone work.

Sometimes composers divide an item of the liturgical text into two or more movements; because of the length of its text, the Dies Iræ is the most frequently divided section of the text (as with Mozart, for instance). The Introit and Kyrie, being immediately adjacent in the actual Roman Catholic liturgy, are often composed as one movement.

Musico-thematic relationships among movements of Requiems can be found as well.

Some settings contain additional texts, such as the devotional motet Pie Jesu (in the settings of Dvořák, Fauré, Duruflé, and Lloyd Webber -- Fauré set it as a soprano solo in the center). Libera me (from the Absolution) and In paradisum (from the burial service, which in the case of a funeral follows after the Mass) conclude some compositions.

Libera me, Domine, de morte æterna, in die illa tremenda, quando coeli movendi sunt et terra, dum veneris iudicare sæculum per ignem. Tremens factus sum ego et timeo, dum discussio venerit atque ventura ira. Dies illa, dies iræ, calamitatis, et miseriæ, dies magna et amara valde. Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis.

("Deliver me, O Lord, from eternal death on that fearful day, when the heavens and the earth are moved, when you come to judge the world with fire. I am made to tremble and I fear, because of the judgment that will come, and also the coming wrath. That day, day of wrath, calamity, and misery, day of great and exceeding bitterness. Grant them eternal rest, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them.")

In paradisum deducant te Angeli; in tuo adventu suscipiant te martyres, et perducant te in civitatem sanctam Ierusalem. Chorus angelorum te suscipiat, et cum Lazaro quondam paupere æternam habeas requiem.

("May angels lead you into paradise; may the martyrs receive you at your coming and lead you to the holy city of Jerusalem. May a choir of angels receive you, and with Lazarus, who once was poor, may you have eternal rest.")

The Pie Jesu combines and paraphrases of the final verse of the Dies irae and the Agnus Dei.

Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem. Dona eis requiem sempiternam.

("O sweet Lord Jesus, grant them rest; grant them everlasting rest.")

Beginning in the 18th century and continuing through the 19th, many composers wrote what are effectively concert requiems, which by virtue of employing forces too large, or lasting such a considerable duration, prevent them being readily used in an ordinary funeral service; the requiems of Gossec, Berlioz, Verdi, and Dvořák are essentially dramatic concert oratorios. A counter-reaction to this tendency came from the Cecilian movement, which recommended restrained accompaniment for liturgical music, and frowned upon the use of operatic vocal soloists.

Requiem is also used to describe any sacred composition that sets to music religious texts which would be appropriate at a funeral, or to describe such compositions for liturgies other than the Roman Catholic Mass.

Among the earliest examples of this type are the German requiems composed in the 17th century by Heinrich Schütz and Michael Praetorius, whose works are Lutheran adaptations of the Catholic requiem, and which provided inspiration for the mighty German Requiem by Brahms.

In the 20th century the requiem evolved in several new directions. The genre of war requiems is perhaps the most notable, which comprise of compositions dedicated to the memory of people killed in wartime. These often include extra-liturgical poems of a pacifist or non-liturgical nature; for example, the War Requiem of Benjamin Britten juxtaposes the Latin text with the poetry of Wilfred Owen.

Lastly, the 20th century saw the development of secular requiems, written for public performance without specific religious observance (e.g., Kabalevsky's War Requiem, to poems by Robert Rozhdestvensky).

Some composers have written purely instrumental works bearing the title of requiem, as exemplified by the most famous of these, Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem.

Igor Stravinsky's Requiem canticles mixes instrumental movements with segments of the "Introit," "Dies irae," "Pie Jesu," and "Libera me."

Hans Werner Henze wrote Das Floß der Medusa in 1968 as a requiem for Che Guevara, although it is properly speaking an oratorio. His Requiem was written in the 1990s, with the traditional title for the movements, but played by instrumentalists without singers.

Ockeghem's Requiem, the earliest to survive, written sometime in the mid-to-late 15th century

Victoria's Requiem of 1603, (part of a longer Office for the Dead)

Mozart's Requiem in D minor (Mozart died before its completion)

Berlioz' Grande Messe des Morts

Verdi's Requiem

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, based on passages from Luther's Bible.

Fauré's Requiem in D minor

Dvořák's Requiem, Op. 89

Britten's War Requiem, which incorporated poems by Wilfred Owen.

Duruflé's Requiem, based almost exclusively on the chants from the Graduale Romanum.

Ligeti's Requiem

Benjamin Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem and Arthur Honegger's Symphonie Liturgique use titles from the traditional Requiem as subtitles of movements.

Requiem Composers

Renaissance

Antoine Brumel

Clemens non Papa

Guillaume Dufay (lost)

Francisco Guerrero

Orlande de Lassus

Cristóbal de Morales

Johannes Ockeghem (the earliest to survive)

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Pierre de la Rue

Claudin de Sermisy

Tomás Luis de Victoria

Baroque

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber

Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Johann Joseph Fux

Claudio Monteverdi (lost)

Michael Praetorius

Heinrich Schütz

Antonio Lotti (Requiem in F Major)

Classical period

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Luigi Cherubini

François-Joseph Gossec

Michael Haydn

Antonio Salieri

Romantic era

Hector Berlioz

Johannes Brahms

Anton Bruckner

Gaetano Donizetti

Antonín Dvořák

Gabriel Fauré

Charles Gounod

Franz Liszt

Max Reger

Camille Saint-Saëns

Robert Schumann

Franz von Suppé

Charles Villiers Stanford

Giuseppe Verdi

20th Century

Benjamin Britten

Vladimir Dashkevich

Maurice Duruflé

Hans Werner Henze

Herbert Howells

György Ligeti

Frank Martin

Krzysztof Penderecki

Ildebrando Pizzetti

Alfred Schnittke

Igor Stravinsky

Toru Takemitsu

John Tavener

Virgil Thomson

Erkki-Sven Tüür

Andrew Lloyd Webber

New Era/21st century

Christopher Rouse

Kentaro Sato

Björk, (Heartbeat aka 'Prayer of the Heart')

Requiems by language (other than purely Latin)

English with Latin

Benjamin Britten

Herbert Howells

German

Michael Praetorius

Heinrich Schütz

Franz Schubert

Johannes Brahms

French, English, German with Latin

Edison Denisov

Polish with Latin

Krzysztof Penderecki

Russian

Sergei Taneyev - Cantata: John of Damascus, Op.1 (Text by Alexey Tolstoy)

Dmitri Kabalevsky - War Requiem (Text by Robert Rozhdestvensky)

[8217 Wilde Alexander / 8210 Thomas Celano / 8201 Thibaut Navarre]