[Arnold Schoenberg at 74, the year of A Survivor from Warsaw (1948)]

"My music is not modern, it is merely badly played."

"I was never revolutionary. The only revolutionary in our time was Strauss!"

Triskaidekaphobia (the fear of the number 13) came honestly to Arnold Schoenberg from day one (b. Arnold Schönberg, September 13, 1874, Vienna, Austria), born to an Ashkenazi Jewish family in the Leopoldstadt district (in earlier times a Jewish ghetto), at Obere Donaustraße 5, and continuing to his death (July 13, 1951).

Although Schoenberg's mother Pauline, a native of Prague, was a piano teacher (his father Samuel, a native of Bratislava, was a shopkeeper), Arnold was largely self-taught, taking only counterpoint lessons with the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, who was to become his first brother-in-law.

In his 20's, Schoenberg converted to Lutheranism in 1898 and lived by orchestrating operettas while composing Two Songs for baritone, Op. 1 (1898); Four Songs, Op. 2 (1899); Six Songs, op. 3 (1899); and the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), op. 4, (1899), which extended the traditionally opposed German romantic traditions of both Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms.

Fellow older post-romantics Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler recognized Schoenberg's significance as a composer --

Strauss when he encountered Schoenberg's Gurre-Lieder (1903), and Mahler after hearing several early works. Strauss turned to a more conservative idiom in his own work after 1909 and at that point dismissed Schoenberg, but Mahler adopted Schoenberg as a protégé and continued to support him even after Schoenberg's style reached a point which Mahler could no longer understand (the elder composer even worried about what would be the fate of the younger after Mahler's passing). Schoenberg, who had initially despised and mocked Mahler's music, was converted by the "thunderbolt" of the Symphony No. 3, which the young firebrand considered a work of genius, and afterwards even spoke of the elder as a saint.

In Gurre-Leider, Schoenberg utilizes sprechstimme (song-speech) -- a form of heightened intonation, where pitches are touched upon and then immediately abandoned in upward or downward glissandi to the next noted pitch. This combination of semi-spoken text with instrumental accompaniment, was known as "melodrama," and it was a genre much in vogue at the end of the 19th Century.

***

Pelleas und Melisande, op. 5 (1903)

Eight Songs for soprano, op. 6 (1903)

String Quartet No. 1, D minor, op. 7 (1904)

***

Schoenberg began teaching harmony, counterpoint and composition in 1904. His first students were Paul Pisk, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg, the latter two ultimately constituting with their teacher a Second or New Viennese School, the first having been that triumvirate of G.F. Haydn, W.A. Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven.

***

Six Songs with orchestra, op. 8 (1905)

Kammersymphonie No. 1 in E Major, op. 9 (1906), premièred without incident the next year.

Two Ballads, op. 12 (1906)

Peace on Earth, op. 13 (1907)

Two Songs, op. 14 (1907)

***

After some early difficulties, Schoenberg began to win public acceptance, as at a Berlin performance in 1907 of the tone poem Pelleas und Melisande.

The summer of 1908, during which his wife Mathilde left him for several months for a young Austrian painter, Richard Gerstl (who committed suicide after her return to her husband and children), marked a distinct change in Schoenberg's work.

It was during the absence of his wife that he composed You Lean Against a Silver-Willow (Du Lehnest wider eine Silberweide), the 13th [!] song in the cycle Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten (The Book of the Hanging Gardens [of Babylon]), op. 15, based on the collection of the same name by the German mystical poet Stefan George. This was the first composition without any reference to a key.

With this work, Schoenberg was at the brink of pantonal (Schoenberg's preferred term) or atonal (the critics' term - the one that caught on!) writing, with full-chromatic pitch collections alluding to no particular key or mode.

Also in this year, he completed String Quartet No. 2 in F-Sharp Minor (with Soprano), op. 10, whose opening movements, though chromatic in color, use traditional key signatures, yet closing sections, also settings of Stefan George, weaken the links with traditional tonality (though both movements end on tonic chords,) and, breaking with previous string-quartet practice, incorporate a soprano vocal line.

During these years, Schoenberg was also a painter of considerable ability, whose pictures were considered good enough to exhibit alongside those of Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky, as part of the Blue Rider expressionist movement.

In a letter written to Ferruccio Busoni in 1909, Schoenberg expresses his reaction against the excesses of romanticism:

"My goal: complete liberation from form and symbols, context and logic.

Away with motivic work!

Away with harmony as the cement of my architecture!

Harmony is expression and nothing more.

Away with pathos!

Away with 24 pound protracted scores!

My music must be short.

Lean! In two notes, not built, but 'expressed.'

And the result is, I hope, without stylized and sterilized drawn-out sentiment.

That is not how man feels; it is impossible to feel only one emotion.

Man has many feelings, thousands at a time, and these feelings add up no more than apples and pears add up. Each goes its own way.

This multicoloured, polymorphic, unlogical nature of our feelings, and their associations, a rush of blood, reactions in our senses, in our nerves; I must have this in my music.

It should be an expression of feeling, as if really were the feeling, full of unconscious connections, not some perception of 'conscious logic.'

Now I have said it, and they may burn me."

***

Three Piano Pieces, op. 11 (1909)

***

Five Pieces for Orchestra, op. 16 (1909)

I. Premonitions

***

Erwartung, op. 17 (1909)

***

During the summer of 1910, Schoenberg wrote his Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony, Schoenberg 1922), which to this day remains an influential study.

Die glückliche Hand (The Lucky Hand or The Golden Touch) for Chorus and Orchestra, op. 18 (1910)

***

Each of the Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke (Six Little Piano Pieces), Op. 19 (1911) is aphoristically short, atonal (broadly speaking), and unique in character. All would loom large for Webern.

I. Leicht, zart (Light, delicate)

II. Langsam (Slow)

III. Sehr langsame (Very slow)

IV. Rasch, aber leicht (Brisk, but light)

V. Etwas rasch (Somewhat brisk)

VI. Sehr langsam (Very slow)

The first five movements were written in a single day, February 11, 1911 (note the numerology once again!). Shortly after Gustav Mahler died later that year in May, Schoenberg wrote the mournful sixth movement. The work was first performed on February 4, 1912 in Berlin, by Louis Closson, and published in 1913 with Universal Edition.

Interestingly, these Little Pieces were composed at the same time that Schoenberg was continuing work on his orchestration of the massive Gurre-Lieder. .

II. Langsam (just how atonal is this piece? -- the G-B ostinato could be an incomplete G chord and the final bass C-E a similar C. How about this analysis of the left hand... C: V i V i V #IVcluster IV bIII bII I, the latter a bizarre IM7 with the right hand)

II. Langsam (just how atonal is this piece? -- the G-B ostinato could be an incomplete G chord and the final bass C-E a similar C. How about this analysis of the left hand... C: V i V i V #IVcluster IV bIII bII I, the latter a bizarre IM7 with the right hand)

III. Sehr langsame

VI. Sehr langsam (with its wonderful, frozen, often quartal harmony; strange resolutions; and final "like a breath" marking)

VI. Sehr langsam (with its wonderful, frozen, often quartal harmony; strange resolutions; and final "like a breath" marking)***

Herzgewächse (Foliage of the Heart) for Soprano, op. 20 (1911)

***

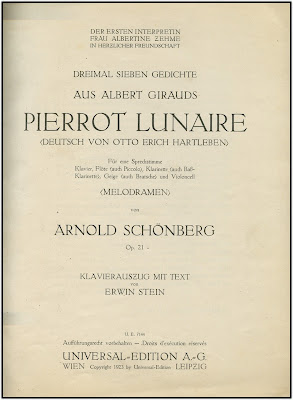

Dreimal Sieben Gedichte aus Albert Girauds 'Pierrot Lunaire', (Three Times Seven Poems from Albert Giraud's 'Pierrot Lunaire'"),

[Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) - Pierrot (c. 1719)]

commonly known as Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot), Op. 21, is a melodrama setting of 21 selected poems from Otto Erich Hartleben's German translation of Belgian-French writer Albert Giraud's cycle of French poems of the same name (1884). The work is between 35 and 40 minutes in duration.

A narrator (voice-type unspecified in the score, but traditionally performed by a soprano) delivers the poems in Sprechstimme.

The work originated in a commission by vocalist Albertine Zehme for a cycle for voice and piano, setting a series of poems by Giraud. Schoenberg began on March 12 and completed the work on July 9, 1912 (noted by one writer as "the barely credible span of six weeks"), having expanded the forces to an ensemble consisting of flute (doubling on a piccolo), clarinet (doubling on bass clarinet), violin (doubling on viola), cello, and piano.

After forty rehearsals, Schoenberg and Zehme (in Columbine dress) gave the premiere at the Berlin Choralion-saal on October 16, 1912. Reaction was predictably mixed, with Webern reporting whistling and laughing, but in the end "it was an unqualified success."

There was some criticism of blasphemy in the texts, to which Schoenberg responded, "If they were musical, not a single one would give a damn about the words. Instead, they would go away whistling the tunes."

The show took to the road throughout Germany and Austria later in 1912.

Pierrot is indeed three groups of seven poems: I. love, sex and religion; II. violence, crime, and blasphemy;

III. Pierrot's return home to Bergamo, with his past haunting him.

I. Mondestrunken (Moon-drunk)

II. Colombine

III. Der Dandy (The Dandy)

IV. Eine blasse Wäscherin (A Pale Washerwoman)

V. Valse de Chopin (Chopin Waltz)

VI. Madonna

VII. Der kranke Mond (The Sick Moon)

VIII. Nacht (Passacaglia) (Night)

IX. Gebet an Pierrot (Prayer to Pierrot)

X. Raub (Theft)

XI. Rote Messe (Red Mass)

XII. Galgenlied (Gallows Song)

XIII. Enthauptung (Beheading)

XIV. Die Kreuze (The Crosses)

XV. Heimweh (Homesick)

XVI. Gemeinheit! (Mean Trick!)

XVII. Parodie (Parody)

XVIII. Der Mondfleck (The Moonfleck)

XIX. Serenade

XX. Heimfahrt (Barcarole) (Journey Home)

XXI. O Alter Duft (O Ancient Scent)

Schoenberg's numerology comes to play again in great use of seven-note motifs throughout the work, while the ensemble (with conductor) comprises seven people. The piece is his opus 21, contains 21 poems, and was begun on March 12, 1912 ("12" as the inversion of "21"). Other key numbers in the work are three and thirteen: each poem consists of thirteen lines.

Pierrot uses a variety of older forms and techniques, including canon, fugue, rondo, passacaglia and free counterpoint. The poetry is a German version of a rondeau of the old French type with a double refrain. Each poem consists of three stanzas of 4 + 4 + 5 lines, with line 1 a Refrain (A) repeated as line 7 and line 13, and line 2 a second Refrain (B) repeated for line 8.

1. A

2. B

3.

4. (everything intervening as "C")

5.

6.

7. A

8. B

9.

10. (everything intervening as "D")

11.

12.

13. A

ABCABDA

The instrumentation of each song is varied such that no two successive numbers have the same combination of timbres. The entire ensemble plays together only during the last poem.

The atonal, expressionistic settings of the text, with their echoes of German cabaret, bring the poems vividly to life.

Pierrot Lunaire is a work that contains many paradoxes: the instrumentalists, for example, are soloists and an orchestra at the same time; Pierrot is both the hero and the fool, acting in a drama that is also a concert piece, performing cabaret as high art and vice versa with song that is also speech; and his is a male role sung by a woman, who shifts between the first and third persons.

I. Mondestrunken (Moon-drunk) (gotta love that ostinato!)

II. Colombine

III. Der Dandy (The Dandy)

IV. Eine blasse Wäscherin (A Pale Washerwoman)

V. Valse de Chopin

VI. Madonna

VI. Madonna

VII. Der kranke Mond (The Sick Moon)

VIII. Nacht (Passacaglia) (Night)

IX. Gebet an Pierrot (Prayer to Pierrot)

[Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) - The Red Look (1909)]

X. Raub (Theft/Loot)

[Black Mass]

XI. Rote Messe (Red Mass)

XII. Galgenlied (Gallows Song)

XIII. Enthauptung (Beheading/Decapitation)

XIV. Die Kreuze (The Crosses / Holy Crosses)

XV. Heimweh (Homesick / Nostalgia)

XVI. Gemeinheit! (Mean Trick! / Atrocity)

XVII. Parodie (Parody)

XVIII. Der Mondfleck (The Moonfleck)

XIX. Serenade

XX. Heimfahrt (Barcarole) (Journey Home / Homeward)

XXI. O Alter Duft (O Ancient Scent)

In 1940, Schoenberg recorded the work with Erika Stiedry-Wagner as the soloist. Other distinguished artists to record the cycle include Bethany Beardslee (Columbia Masterworks M2S 679) and Jan DeGaetani (1970).

The jazz singer Cleo Laine recorded Pierrot Lunaire in 1974, a version nominated for a classical Grammy Award.

The quintet of instruments used in Pierrot became the core ensemble for the The Fires of London, who formed in 1965 as The Pierrot Players to perform the work, and continued to concertize with a varied classical and contemporary repertory. The group performed works arranged for these instruments and commission new works especially to take advantage of this ensemble's instrumental colors, until it disbanded in 1987.

Over the years, other groups have continued to use this instrumentation professionally (current groups include Da Capo Chamber Players, eighth blackbird, Sounds New, the Emperion Players, and Earplay), and have built a large repertoire for the ensemble.

***

Four Songs for Voice and Orchestra, op. 22 (1913)

***

The Vienna première of the Gurre-Lieder on February 13[!], 1913 [!!], received an ovation that lasted a quarter of an hour, with Schoenberg give a laurel crown.

But the next month, on March 31 [the inversion of 13!] 1913 when Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony No. 1 was performed, in a concert featuring works by Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Alexander von Zemlinsky, and Gustav Mahler, the thunderous applause contended with hisses and laughter during Webern's Six Pieces, op. 6. Though Zemlinsky's Four Maeterlinck Songs calmed the audience somewhat, according to a contemporary newspaper report, after Schoenberg's op. 9 "one could hear the shrill sound of door keys among the violent clapping and in the second gallery the first fight of the evening began". Later in the concert, during a performance of the Altenberg Lieder by Berg, fighting broke out after Schoenberg interrupted the performance to threaten removal by the police of any troublemakers. Mahler's Kindertotenlieder had to be cancelled after the police were called in.

World War I brought a crisis in development. Military service disrupted Schoenberg's life, such that was unable to work uninterrupted or over a period of time, and as a result he left many unfinished works and undeveloped "beginnings." At the age of 42 he found himself in the army. On one occasion, a superior officer demanded to know if he was "this notorious Schoenberg, then"; Schoenberg replied: "Beg to report, sir, yes. Nobody wanted to be, someone had to be, so I let it be me" (a reference to Schoenberg's apparent "destiny" as the "Emancipator of Dissonance").

The deteriorating relation between contemporary composers and the public led him to found the Society for Private Musical Performances (Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen in German) in Vienna in 1918. His aim was grandiose but scarcely selfish; he sought to provide a forum in which modern musical compositions could be carefully prepared and rehearsed, and properly performed under conditions protected from the dictates of fashion and pressures of commerce. From its inception through 1921, when it ended because of economic reasons, the Society presented 353 performances to paid members, sometimes at the rate of one per week, and during the first year and a half, Schoenberg did not allow any of his own works to be performed. Instead, audiences at the Society's concerts heard difficult contemporary compositions by Scriabin, Debussy, Mahler, Webern, Berg, Reger, and other leading figures of early 20th-century music.

By 1923, Schoenberg had developed a means of order which would enable his musical texture to become simpler and clearer, and this resulted in the "method of composition with twelve tones" in which the twelve pitches of the octave are regarded as equal, and no one note or tonality is given the emphasis it occupied in classical harmony. He regarded it as the equivalent in music of Albert Einstein's discoveries in physics, and Schoenberg announced it characteristically, during a walk with his friend Josef Rufer, when he said "I have made a discovery which will ensure the supremacy of German music for the next hundred years."

This 12-tone, or dodecaphonic, system (an earlier scheme from Josef Matthias Hauer failed to catch on) was given the alternative name serialism by René Leibowitz and Humphrey Searle in 1947.

Works in this period include Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23 (1923 - note date and opus!); Serenade, Op. 24 (1923), Piano Suite, Op. 25 (1923), and Wind Quintet, Op. 26 (1924).

Following the 1924 death of composer Ferruccio Busoni, Schoenberg was appointed Director of a Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, taking up the post in 1926 after a bout with ill health. Among his notable students during this period were the composers Roberto Gerhard, Nikos Skalkottas, and Josef Rufer.

***

Four Pieces, op. 27 (1925)

Suite, op. 29 (1925)

***

Schoenberg was not fond of Russian (by this point, neoclassical) composer Igor Stravinsky, and in 1926 wrote a poem titled Der Neue Klassizismus (in which he derogates Neoclassicism and obliquely refers to Stravinsky as "Der kleine Modernsky"), utilized as text for the third of his Drei Satiren, op. 28.

Other works in this period include String Quartet No. 3, Op. 30 (1927); Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 (1928); Von Heute auf Morgen (From Today to Tomorrow) opera in one act, Op. 32 (1928); Accompanying Music to a Film Scene, Op. 34 (1930); Six Pieces for Male Chorus, Op. 35 (1930, one of which, pertaining to cattle slaughter, presages the gas chambers); and Piano Pieces, Op. 33a & b (1931); and Three Songs, Op. 48 (1933)

Schoenberg continued in his Berlin position until the election of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis in 1933, when his music was labeled (alongside jazz), as degenerate art, such that he was dismissed and forced into exile. His unfinished Moses und Aron, one of the first 12-tone operas, also dates to this year, and signals again his fear of the dreaded 13 (the original title being Moses und Aaron, 12+1 letters). Contrary to Schoenberg's reputation for strictness, this work, as others, draws on freely atonal or tonal materials.

The refugee emigrated to Paris, where he reaffirmed his Jewish faith; and thence to the United States in 1934, changing the spelling of his name from Schönberg. His first teaching position in the U.S. was at the Malkin Conservatory in Boston. He was then wooed by Los Angeles, where he taught at the University of Southern California and the University of California, Los Angeles, both of which later named a music building on their respective campuses Schoenberg Hall.

The expatriate settled in Brentwood Park, where he befriended fellow composer (and tennis partner) George Gershwin, declining to teach him, after he noted their disparate incomes (Gershwin's music was by far more money-making). Film composer Leonard Rosenman studied with Schoenberg at this time, as did John Cage, Lou Harrison, and Owen Reed.

Perhaps it is less of a surprise that Schoenberg became interested in movies during these years, particularly Hopalong Cassidy films, which Paul Buhle and David Wagner attribute to the films' left-wing screenwriters - a rather odd claim in light of Schoenberg's statement that he was a bourgeois turned monarchist.

During this final period Schoenberg composed a number of works, including a formidable Violin Concerto, Op. 36 (1936); String Quartet No. 4, Op. 37 (1936); and Kammersymphonie (Chamber Symphony) No. 2, E-Flat Minor, Op. 38 (1939).

The composer feared he would die during a year that was a multiple of 13. He so dreaded his 65th birthday in 1939 that his horoscope was prepared by composer-astrologer Dane Rudhyar, who told Schoenberg that the year was dangerous, but not fatal.

Somehow he carried on, writing Kol Nidre, Op. 39, for chorus and orchestra (1938); and Variations on a Recitative for Organ, Op. 40 (1941)

After becoming a naturalized citizen of the United States, Schoenberg composed Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, for Voice, Piano, and String Quartet, Op. 41 (1942); Piano Concerto, Op. 42 (1942); Theme and Variations for Band, Op. 43a (1943, transcribed for Orchestra as Op. 43b); Prelude to “Genesis” for Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 44 (1945); and String Trio, Op. 45 (1946).

***

A Survivor from Warsaw, Op. 46 (1947)

Beginning, surreal fanfares, sprechstimme, and a haunting premonition of the Shema Israel

Ending, with the full defiant statement of the creed

***

Fantasy for Violin and Piano, op. 47 (1949).

Schoenberg's serial technique of composition with 12 notes became one of the most central and polemical issues among American and European musicians during the mid- to late-20th century. Beginning in the late 1940's and continuing to the present day, composers such as Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono and Milton Babbitt have extended Schoenberg's legacy in increasingly radical directions. The major cities in the United States (such as Los Angeles, New York, and Boston) have been hosts for historically significant performances of Schoenberg's music, with advocates such as Babbitt and Schoenberg's own pupils, who have taught at major American schools (e.g. Leonard Stein at USC, UCLA and CalArts; Richard Hoffmann at Oberlin; Patricia Carpenter at Columbia; and Leon Kirchner and Earl Kim at Harvard). In Europe, the work of René Leibowitz has had a measurable influence in spreading Schoenberg's musical legacy outside of Germany and Austria.

***

Dreimal Tausend Jahre (Three Times a Thousand Years), Op. 50a (1949)

Psalm 130 “De Profundis”, Op. 50b (1950)

Modern Psalm, Op. 50c (1950, unfinished)

***

Superstition may have triggered Schoenberg's death. In 1950, on his 76 (7+6=13) birthday, an astrologer wrote Schoenberg a note warning him that the year was a critical one. This stunned and depressed the composer, for up to that point he had only been wary of multiples of 13 and never considered adding the digits of his age.

On Friday, 13 July 1951, Schoenberg stayed in bed -- sick, anxious and depressed. In a letter to Schoenberg's sister Ottilie, dated 4 August 1951, his wife, Gertrud, reported "About a quarter to 12 I looked at the clock and said to myself: another quarter of an hour and then the worst is over. Then the doctor called me. Arnold's throat rattled twice, his heart gave a powerful beat and that was the end." Gertrud reported the next day in a telegram to her sister-in-law Ottilie that Arnold died at 11:45pm, although rumor has it that it was actually 13 minutes before midnight....

[Schoenberg's grave in the Zentralfriedhof, Vienna]

Arnold Schoenberg's daughter, Nuria Dorothea, married Luigi Nono in 1955.

Many Schoenberg practices, including the formalization of compositional method, and his habit of openly inviting audiences to think analytically, are echoed in avant-garde musical thought throughout the 20th and into the 21 Century. Schoenberg's often polemical views of music history and aesthetics were crucial to many later musicologists and critics, including Theodor Adorno, Charles Rosen, and Carl Dahlhaus.

The Schoenberg archival legacy is collected at the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna.

[8874 Holst / 8874 Schoenberg / 8873 Handy]