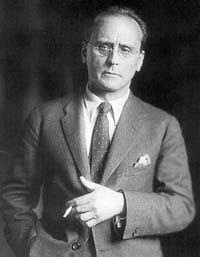

Edgard [Victor Achille Charles] Varèse (December 22, 1883, Paris, France - November 6, 1965) was an innovative French-born composer who spent the greater part of his career in the United States.

After he arrived in the U.S.A. he commonly used the form "Edgar" for his first name but reverted to "Edgard," not entirely consistently, from the 1940's.

Varèse's music features an emphasis on timbre and rhythm. He was the inventor of the term "organized sound", a phrase meaning that certain timbres and rhythms can be grouped together, sublimating into a whole new definition of sound. His use of new instruments and electronic resources led to his being known as the "Father of Electronic Music" while Henry Miller described him as "The stratospheric Colossus of Sound."

A few weeks after his birth, Varèse was sent to be raised by his great-uncle's family in the small town of Villars in Burgundy. There he developed an intense attachment to his maternal grandfather, Claude Cortot. Through his mother's family he was related to the pianist Alfred Cortot. His affection for his grandfather outshone anything he would ever feel for his own parents. In fact, from his earliest years Varèse's relationship with his father Henri was extremely antagonistic, developing into what could fairly be called a firm and life-long hatred.

Visitors to Varèse's childhood village of La Villars, deep in the Burgundian countryside, sometimes meet locals who remember him. If they call at the actual house they are shown up to Varèse's own bedroom. From the window they instantly gain an insight into the young Varèse's musical influences: the rural scene stretches to the horizon but immediately beneath the window is the railway line and just beyond that the busy waterway with its chugging cargo boats.

Reclaimed by his parents in the late 1880's, in 1893 young Edgard was forced to relocate with them to Turin, Italy. It was here that he had his first real musical lessons, with the long-time director of Turin's conservatory, Giovanni Bolzoni. Never comfortable with Italy, and given his oppressive home-life, a physical altercation with his father forced the situation and Varèse left home for Paris in 1903.

From 1904 he was a student at the Schola Cantorum (founded by pupils of César Franck), where his teachers included Albert Roussel; afterwards he went to study composition with Charles Widor at the Paris Conservatoire. From this period he composed a number of ambitious orchestral works, but these were only performed by Varèse in piano transcriptions, such as his Rhapsodie romane of about 1905, inspired by the Romanesque architecture of the cathedral of St. Philibert in Tournus. He moved to Berlin in 1907 and in the same year married the actress Suzanne Bing. They had one child, a daughter. They divorced in 1913.

During these years, Varèse became acquainted with Satie, Richard Strauss, Debussy, and Busoni, the last two being particular influences on him at the time. He also gained the friendship and support of Romain Rolland and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, whose Oedipus und die Sphinx he began setting as an opera that was never completed. The first performance of his symphonic poem Bourgogne in Berlin in 1910, the only one of his early orchestral works to be properly performed, caused a scandal. After being invalided out of the French Army during World War I, he moved to the United States in 1915. In 1917 Varèse made his debut in America conducting the Grand Messe des Morts by Berlioz.

He spent the first few years in the United States, where he was a Romany Marie's café regular in Greenwich Village, meeting important contributors to American music, promoting his vision of new electronic art music instruments, conducting orchestras, and founding the New Symphony Orchestra, which was short-lived.

It was also about this time that Varèse began work on his first composition in the United States, Amériques, which was finished in 1921 but would remain unperformed until 1926.

Virtually all the works he had written in Europe were either lost or destroyed in a Berlin warehouse fire, so in the USA he was starting again from scratch. The only surviving work from his early period appears to be the song Un grand sommeil noir, a setting of Verlaine (He still retained Bourgogne, but destroyed the score in a fit of depression many years later). It was at the completion of this work that Varèse, along with Carlos Salzedo, founded the International Composers' Guild, dedicated to the performances of new compositions of both American and European composers. The ICG's manifesto in July 1921 included the statement that

"The present day composers refuse to die. They have realised the necessity of banding together and fighting for the right of each individual to secure a fair and free presentation of his work."

***

Ameriques (1921)

Offrandes (1921)

***

In 1922, Varèse visited Berlin where he founded a similar German organisation with Busoni.

Varèse composed many of his pieces for orchestral instruments and voices for performance under the auspices of the ICG during its six-year existence. Specifically, during the first half of the 1920's, he composed Offrandes, Hyperprism, Octandre, and Intégrales.

***

Hyperprism (1923)

Octandre (1924)

I

II

III

Integrales (1925)

Arcana (1927)

***

In his formative years he was greatly impressed by Medieval and Renaissance Music (in his career he founded and conducted several choirs devoted to this repertoire) and the music of Scriabin, Satie, Debussy, Berlioz and Richard Strauss. There are also clear influences or reminiscences of Stravinsky's early works, specifically Petrushka and The Rite of Spring, on Arcana.

He claimed to have been inspired by the writings on music of Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński, and especially the Polish savant's statement that the object of music is "the corporealization of the intelligence that is in sound." He was also impressed by the ideas of Busoni, who christened him L'illustro futuro.

He took American citizenship in October 1927.

In 1928, Varèse returned to Paris to alter one of the parts in Amériques to include the recently constructed Ondes Martenot. Around 1930, he composed his most famous non-electronic piece entitled Ionisation, the first to feature solely percussion instruments. Although it was composed with pre-existing instruments, Ionisation was an exploration of new sounds and methods to create them.

***

Ionisation (1931)

***

In 1933, while Varèse was still in Paris, he wrote to the Guggenheim Foundation and Bell Laboratories in an attempt to receive a grant to develop an electronic music studio. His next composition, Ecuatorial, completed in 1934, contained parts for fingerboard theremin cellos, and Varèse, anticipating the successful receipt of one of his grants, eagerly returned to the United States to finally realize his electronic music.

***

Ecuatorial (1934)

***

Varèse wrote his Ecuatorial for two fingerboard Theremins, bass singer, winds and percussion in the early 1930's. It was premiered on April 15 1934, under the baton of Nicolas Slonimsky.

Then Varèse left New York City, where he had lived since 1915, and moved to Santa Fe, San Francisco and Los Angeles. In 1936 he wrote Density 21.5. By the time Varèse returned in late 1938, Leon Theremin had returned to Russia. This devastated Varèse, who had hoped to work with Theremin on a refinement of his instrument. Varèse had also promoted the theremin in his Western travels, and demonstrated one at a lecture at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque on November 12 1936. The University of New Mexico has an RCA theremin, which may be the same instrument.

***

Density 21.5 (1936)

***

He was approached by music producer Jack Skurnick resulting in EMS Recordings #401. The record was the first release of Integrales, Density 21.5, Ionization, and Octandre and featured Rene le Roy, flute, the Julliard Percussion Orchestra and the New York Wind Ensemble conducted by Frederic Waldman. Frank Zappa and others have acknowledged the influence of this recording.

From the late 1920's to the end of the 1930's, Varèse's principal creative energies went into two ambitious projects which were never realized, and much of whose material was destroyed, though some elements from them seem to have gone into smaller works. One was a large-scale stage work called different things at different times, but principally The One-All-Alone or Astronomer (L’Astronome). This was originally to be based on North American Indian legends; later it became a futuristic drama of world catastrophe and instantaneous communication with the star Sirius. This second form, on which Varèse worked in Paris in 1928–1932, had a libretto by Alejo Carpentier, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Robert Desnos. According to Carpentier, a substantial amount of this work was written but Varèse abandoned it in favour of a new treatment in which he hoped to collaborate with Antonin Artaud. Artaud's libretto Il n’ya plus de firmament was written for Varèse's project and sent to him after he had returned to the USA but by this time Varèse had turned to a second huge project.

This second project was to be a choral symphony entitled Espace. In its original conception the text for the chorus was to be written by André Malraux. Later Varèse settled on a multi-lingual text of hieratic phrases to be sung by choirs situated in Paris, Moscow, Peking and New York, synchronized to create a global radiophonic event. Varèse sought input on the text from Henry Miller, who suggests in The Air-Conditioned Nightmare that this grandiose conception -- also ultimately unrealized -- eventually metamorphosed into Déserts. With both these huge projects Varèse felt ultimately frustrated by the lack of electronic instruments to realize his aural visions. Nevertheless he used some of the material from Espace in his short Étude pour Espace, virtually the only work that had appeared from his pen for over ten years when it was premiered in 1947.

When, in the late 1950's, Varèse was approached by a publisher about making Ecuatorial available, there were very few theremins -- let alone fingerboard theremins -- to be found, so he rewrote/relabelled the part for Ondes Martenot. This new version was premiered in 1961.

Louise Varèse, American-born wife of the composer, was a celebrated translator of French poetry whose versions of the work of Arthur Rimbaud for James Laughlin's New Directions imprint were particularly influential.

***

Deserts (1954)

***

By the early 1950's, Varèse was in dialogue with a new generation of composers, such as Boulez and Dallapiccola. When he returned to France to finalize the tape sections of Déserts, Pierre Schaeffer helped arrange for suitable facilities. The first performance of the combined orchestral and tape sound composition came as part of an ORTF broadcast concert, between pieces by Mozart and Tchaikovsky and received a hostile reaction.

Le Corbusier was commissioned by Philips to present a pavilion at the 1958 World Fair and insisted (against the sponsors' resistance) on working with Varèse, who developed his Poème électronique for the venue, where it was heard by an estimated two million people. Using 400 speakers separated throughout a series of rooms, Varèse created a sound and space installation geared towards experiencing sound as you move through space. Received with mixed reviews, this piece challenged audience expectations and traditional means of composing, breathing life into electronic synthesis and presentation.

Poeme Electronique (1958)

In 1962 he was asked to join the Royal Swedish Academy, and in 1963 he received the premier Koussevitzky International Recording Award.

According to George Perle "his partitioning of the octave in the first ten bars places Varèse with Scriabin and the Schoenberg circle among the revolutionary composers whose work initiates the beginning of a new mainstream tradition in the music of our century."

Varèse's best known student is the Chinese-born composer Chou Wen-chung (b. 1923), who met Varèse in 1949 and assisted him in his later years. He became the executor of Varèse's estate following the composer's death and edited and completed a number of Varèse's works. He is professor emeritus of composition at Columbia University. Other pupils were Colin McPhee and André Jolivet.

Composers who have claimed, or can be demonstrated to have been influenced by Varèse include Harrison Birtwistle, Pierre Boulez, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Roberto Gerhard, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, Frank Zappa, and William Grant Still.

Varèse's emphasis on timbre, rhythm, and new technologies was an inspiration to a whole generation of musicians who came of age during the 1960's and 1970's. One of Varèse's biggest fans was the American guitarist and composer Frank Zappa, who, upon hearing a copy of The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse, Vol. 1, which included Intégrales, Density 21.5, Ionisation, and Octandre, became obsessed with the composer's music. On his 15th birthday, December 21, 1955, Zappa's mother, Rosemarie, allowed him a call to Varèse as a present. At the time Varèse was in Brussels, Belgium, so Zappa spoke to Varèse's wife Louise instead. Eventually Zappa and Varèse spoke on the phone, and they discussed the possibility of meeting each other, although this meeting never took place. Zappa also received a letter from Varèse. Varèse's spirit of experimentation and redefining the bounds of what was possible in music lived on in Zappa's long and prolific career. Zappa's final project was The Rage and the Fury, a recording of the works of Varèse.

Another admirer was the rock/jazz group Chicago, whose Pianist/keyboardist Robert Lamm credited Varèse with inspiring him to write many number one hits. In tribute, one of Lamm's songs was called "A Hit By Varèse".

The record label Varèse Sarabande Records is named after him.

Some of Edgard Varèse's later works make use of the "Idée Fixe" a fixed theme, repeated certain times in a work. The "Idée Fixe" is generally not transposed, differentiating it from the leitmotiv, used by Richard Wagner.

[8885 Berg / 8883 Varese / 8883 Webern]