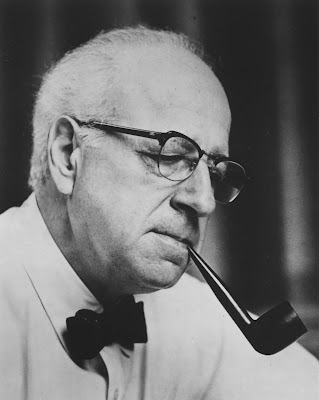

[Bernstein in 1944]

Leonard Bernstein (b. Louis Bernstein, August 25, 1918, Lawrence, MA - October 14, 1990) was born to a Polish-Jewish family from Rivne, now Ukraine. His grandmother insisted his first name be Louis, but his parents always called him Leonard, as they liked the name better. He had his name changed to Leonard officially when he was 15.

His father, Sam Bernstein, was a businessman, and initially opposed young Leonard's interest in music. Despite this, the elder Bernstein frequently took him to orchestra concerts. At a very young age, Leonard heard a piano performance and was immediately captivated; he subsequently began learning the piano. As a child, Bernstein attended the Garrison School and Boston Latin School.

After graduation from Boston Latin School in 1934 Bernstein attended Harvard University, where he studied music with Walter Piston and was briefly associated with the Harvard Glee Club.

One of this friends at Harvard was Donald Davidson, considered one of the leading philosophers of the 20th century, with whom he played piano four hands. Bernstein wrote and conducted the musical score for the production which Davidson mounted of Aristophanes's The Birds in the original Greek. Some of this music was later to be reused in Bernstein's ballet Fancy Free.

After completing his studies at Harvard he enrolled in the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he received the only "A" grade Fritz Reiner ever awarded in his class on conducting. During his time at Curtis, Bernstein also studied piano with Isabella Vengerova. Later in life he confessed it took him years to unlearn the incorrect technique she'd taught him.

During his young adult years in New York City, Bernstein enjoyed an exuberant social life that included relationships with both men and women.

***

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, 1939

***

In 1940, he began his study at the Boston Symphony Orchestra's summer institute, Tanglewood, under the orchestra's conductor, Serge Koussevitzky. Bernstein later became Koussevitzky's conducting assistant. He would later dedicate his Symphony No. 2 to Koussevitzky.

***

Symphony No. 1 ("Jeremiah"), 1942

***

On November 14, 1943, having recently been appointed assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, he made his conducting debut on last minute notification, and without any rehearsal, after Bruno Walter came down with the flu. The next day, The New York Times editorial remarked, "It's a good American success story. The warm, friendly triumph of it filled Carnegie Hall and spread far over the air waves."

He was an immediate success and became instantly famous because the concert was nationally broadcasted. The soloist on that historic day was Joseph Schuster, solo cellist of the New York Philharmonic, who played Richard Strauss's Don Quixote. Since Bernstein had never conducted the work before, Bruno Walter coached him on it prior to the concert. It is possible to hear this remarkable event thanks to a transcription recording made from the CBS radio broadcast that has since been issued on CD.

***

I Hate Music: A Cycle of Five Kids Songs for Soprano and Piano, 1943

Fancy Free (ballet), 1944

On the Town (musical), 1944

Hashkiveinu for Solo Tenor, Mixed Chorus and Organ, 1945

Facsimile (ballet), 1946

***

After World War II Bernstein's career on the international stage began to flourish. In 1946 he conducted his first opera, the American premiere of Benjamin Britten's Peter Grimes, which had been a Koussevitzky commission.

In 1947, Bernstein conducted in Tel Aviv for the first time, beginning a life-long association with Israel.

***

La Bonne Cuisine: Four Recipes for Voice and Piano, 1948

***

He conducted the world première of the Turangalîla-Symphonie by Olivier Messiaen, in 1949

***

Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs for Solo Clarinet and Jazz Ensemble, 1949

Symphony No. 2 ("The Age of Anxiety"), (after W. H. Auden) for Piano and Orchestra, 1949 (revised in 1965)

Peter Pan (songs, incidental music), 1950

***

Bernstein recorded extensively from the 1950's until just a few months before his death. Aside from a few early recordings in the mid-1940's for RCA Victor, Bernstein recorded primarily for Columbia Masterworks Records, especially when he was music director of the New York Philharmonic. Many of these performances have been digitally remastered and reissued by Sony as part of the Royal Edition and Bernstein Century series.

When Koussevitzky died in 1951, Bernstein became head of the orchestral and conducting departments at Tanglewood, holding this position for many years.

That same year, Bernstein conducted the New York Philharmonic in the world premiere of the Symphony No. 2 of Charles Ives. The composer, old and frail, was unable to attend the concert, but listened to the broadcast on the radio with his wife, Harmony. They both marveled at the enthusiastic reception of his music, which had actually been written between 1897 and 1901, but until then had never been performed.

After a long internal struggle and a turbulent on-and-off engagement, he married Chilean actress Felicia Montealegre Cohn on September 9, 1951, reportedly in order to increase his chances of obtaining the chief conducting position with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Dimitri Mitropoulos, conductor of the New York Philharmonic and Bernstein's mentor, advised him that marrying would help counter the gossip about him and appease the conservative BSO board.

Leonard and Felicia had three children, Jamie, Alexander, and Nina. During his married life, Bernstein tried to be as discreet as possible with his extramarital liaisons. But as he grew older, and as the Gay Liberation movement made great strides, Bernstein became more emboldened, eventually leaving Felicia to live with his lover Tom Cochran. Some time after, Bernstein learned that his wife was diagnosed with lung cancer. Bernstein moved back in with his wife and cared for her until she died.

It has been suggested that Bernstein was actually bisexual — an assertion supported by comments Bernstein himself made about not preferring any particular cuisine, musical genre, or form of sex -- and it has been alleged that he was conflicted between his devotion to his family and his gay desires, but Arthur Laurents (Bernstein's collaborator in West Side Story), said that Bernstein was simply "a gay man who got married. He wasn't conflicted about it at all. He was just gay."

Shelly Rhoades Perle, another friend of Bernstein’s, said that she thought "he required men sexually and women emotionally."

Bernstein was also a visiting music professor in the early 1950's, and founder/head of the Creative Arts Festivals at Brandeis University from 1952 onward. The festival was named after him in 2005, becoming the Leonard Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts.

***

Trouble in Tahiti (opera in one act), 1952

Wonderful Town (musical), 1953

On the Waterfront (film score), 1954

Serenade for Solo Violin, Strings, Harp and Percussion (after Plato's Symposium), 1954

The Lark (incidental music), 1955

Candide (operetta), 1956 (new libretto in 1973, operetta revised in 1989)

Overture

Chorale 1: Westfalia

Chorale 2: Universal Good

West Side Story (musical), 1957

V. Maria

VI. America

XI. Quintet

XII. The Rumble

XIII. Cool

XV. Somewhere (Finale)

***

In 1957, he conducted the inaugural concert of the Mann Auditorium in Tel Aviv, Israel, and subsequently made many recordings there.

Bernstein was named Music Director of the New York Philharmonic in 1957 and began his tenure in that position in 1958, a post he held until 1969, although he continued to conduct and make recordings with that orchestra for the rest of his life. He became a well-known figure in the US through his series of 53 televised Young People's Concerts for CBS, which grew out of his Omnibus programs that CBS aired in the early 1950's. His first Young People's Concert was televised only a few weeks after his tenure as principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic began.

Bernstein became as famous for his educational work in those concerts as for his conducting. Some of his music lectures were released on records, with several of these albums winning Grammy awards. To this day, the Young People's Concerts series remains the longest running group of classical music programs ever shown on commercial television. They ran from 1958 to 1972. More than 30 later, twenty-five of them were rebroadcast on the cable channel Trio, and released on DVD.

***

The Firstborn (incidental music), 1958

Brass Music, 1959

***

In 1959 he took the New York Philharmonic on a tour of Europe and the Soviet Union, portions of which were filmed by CBS. A major highlight of the tour was Bernstein's performance of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5, in the presence of the composer, who came on stage at the end to congratulate Bernstein and the musicians. In October, when Bernstein and the orchestra returned to New York, they recorded the symphony for Columbia. He made two recordings of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7 ("Leningrad"), one with the New York Philharmonic in the 1960's, and another one in 1988 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the only recording he ever made with them (along with Shostakovich's Symphony No. 1, also recorded live in concerts at Orchestra Hall in Chicago at that time).

He was considered especially accomplished with the works of Gustav Mahler, Aaron Copland, Johannes Brahms, Dmitri Shostakovich, George Gershwin (especially the Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris), and of course with the performances of his own works. Bernstein never conducted a performance of Gershwin's Piano Concerto in F, nor Porgy and Bess. However, he did discuss Porgy in his article, Why Don't You Run Upstairs and Write a Nice Gershwin Tune?, originally published in the New York Times and later reprinted in his 1959 book The Joy of Music.

He had a gift for rehearsing an entire Mahler symphony by acting out every phrase for the orchestra to convey the precise meaning, and of emitting a vocal manifestation of the effect required, with a subtly professional ear that missed nothing.

Bernstein influenced many conductors who are performing now, such as Marin Alsop, Alexander Frey, John Mauceri, Seiji Ozawa, Carl St.Clair, and Michael Tilson Thomas. Ozawa made his first network television debut as guest conductor on one of the Young People's Concerts.

In 1960 Bernstein began the first complete cycle of recordings in stereo of all nine completed symphonies by Gustav Mahler, with the blessings of the composer's widow, Alma. The success of these recordings, along with Bernstein's concert performances, greatly revived interest in Mahler, who had briefly been music director of the New York Philharmonic late in his life. That same year, Bernstein conducted an LP of his own score for the 1944 musical On The Town, in stereo, the first such recording of the score ever made, for Columbia Masterworks Records. Unlike his later recordings of his own musicals, this was originally issued as a single LP rather than a 2-record set. It was later issued on CD. The recording featured several members of the original Broadway cast, including Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

In one storied incident, in April 1962, Bernstein appeared on stage before a performance of the Brahms Piano Concerto in D Minor, Op. 15. The soloist was the legendary pianist Glenn Gould. During rehearsals, Gould had argued for tempi much broader than normal, which did not reflect Bernstein's concept of the music. Bernstein gave a brief address to the audience stating,

"Don't be frightened Mr. Gould is here [audience laughter]. He will appear in a moment. I'm not- um- as you know in the habit of speaking on any concert except the Thursday night previews, but a curious situation has arisen, which merits, I think, a word or two. You are about to hear a rather, shall we say, unorthodox performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto, a performance distinctly different from any I've ever heard, or even dreamt of for that matter, in its remarkably broad tempi and its frequent departures from Brahms' dynamic indications. I cannot say I am in total agreement with Mr. Gould's conception and this raises the interesting question: "What am I doing conducting it?" [mild laughter from the audience] I'm conducting it because Mr. Gould is so valid and serious an artist that I must take seriously anything he conceives in good faith and his conception is interesting enough so that I feel you should hear it, too. But the age old question still remains: 'In a concerto, who is the boss [audience laughter]- the soloist or the conductor?" [Audience laughter grows louder] The answer is, of course, sometimes the one and sometimes the other depending on the people involved. But almost always, the two manage to get together by persuasion or charm or even threats [audience laughs] to achieve a unified performance. I have only once before in my life, had to submit to a soloist's wholly new and incompatible concept and that was the last time I accompanied Mr. Gould [audience laughs loudly]. But, but THIS time, the descrepencies between our views are so great that I feel I must make this small disclaimer. Then why, to repeat the question, am I conducting it? Why I do I not make a minor scandal -- get a substitute soloist, or let an assistant conduct? Because I am FASCINATED, glad to have the chance for a new look at this much played work; Because, what's more, there are moments in Mr. Gould's performance that emerge with astonishing freshness and conviction. Thirdly, because we can ALL learn something from this extraordinary artist who is a THINKING performer, and finally because there IS in music what Dimitri Mitropoulos used to call "the SPORTIVE element" [mild audience laughter] that FACTOR of curiosity, adventure, experiment, and I can assure you that it HAS been an adventure this week [audience laughter] collaborating with Mr. Gould on this Brahms concerto and it's in this spirit of adventure that we now present it to you."

This speech was subsequently interpreted by NY Times Critic Harold Schoenberg as an attack on Gould, but Bernstein always denied that this had been his intent. Throughout his life he professed enormous admiration and personal friendship for Gould.

During his New York Philharmonic directorship, Bernstein was also responsible for introducing the symphonies of the Danish composer Carl Nielsen to American audiences, leading to a revival of interest in this composer whose reputation had previously been mostly regional. Bernstein recorded three of Nielsen's symphonies (No. 2, 4 and 5) with the Philharmonic, and recorded the composer's Symphony No. 3 with a Danish orchestra after a critically-acclaimed public performance there.

***

Symphony No. 3 ("Kaddish"), for Orchestra, Mixed Chorus, Boys' Choir, Speaker and Soprano Solo, 1963 (revised in 1977)

***

Chichester Psalms for Boy Soprano (or Countertenor), Mixed Chorus and Orchestra, 1965

I.

II.

III.

The bluesy (Mi / Me) melody of the boy soprano solo (6 bars) in the second movement has varied rhythms over a basic Do-Re-Mi --

A:

Sol Re Do Re Mi Do Re Mi Do Re Do Me Do Re Do --

and Please Mr. Postman altered harmony...

I vi IV ii V I...

... with an inevitably descending bass and the potential of two common-tones at a time for a stretch (since the harmony moves in thirds).

***

In 1967 he conducted a concert on Mt. Scopus to commemorate the reunification of Jerusalem.

In 1966 he made his debut at the Vienna State Opera conducting Luchino Visconti's production of Verdi's Falstaff, with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Falstaff.

In 1970 he returned to the Vienna State Opera for Otto Schenk's production of Beethoven's Fidelio.

Beginning in 1970, Bernstein conducted the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, with which he re-recorded many of the pieces that he had previously taped with the New York Philharmonic, including sets of the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms and Schumann. Some of the Mahler symphony recordings from Bernstein's second cycle for Deutsche Grammophon were also made with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Bernstein was highly regarded as a conductor among many musicians, including the members of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, evidenced by his honorary membership, the London Symphony Orchestra, of which he was President, and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, with whom he appeared regularly as guest conductor.

Later that year, Bernstein wrote and narrated a 90-minute program filmed on location in and around Vienna, featuring the Vienna Philharmonic with such artists as Plácido Domingo, who in his first television appearance performed as the tenor soloist in Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. The program, first telecast in 1970 on Austrian and British television, and then on CBS on Christmas Eve 1971, was intended as a celebration of Beethoven's 200th birthday. The show made extensive use of the rehearsals and finished performance of the Otto Schenk production of Fidelio. Originally entitled Beethoven's Birthday: A Celebration in Vienna, the show, which won an Emmy, was telecast only once on U.S. commercial television, and remained in CBS's vaults, until it resurfaced on A&E shortly after Bernstein's death - under the new title Bernstein on Beethoven: A Celebration in Vienna. It was immediately issued on VHS under that title, and in 2005 was issued on DVD.

During the 1970's, Bernstein recorded most of his own symphonic music with the Israel Philharmonic.

***

Mass (theatre piece for singers, players and dancers), 1971

I. Devotions Before Mass

1. Kyrie

2. Simple Song

II. First Introit

1. Prefatory Prayers (Kyrie March)

III. Second Introit

2. Chorale "Almighty Father"

IV. Confession

2. Trope - I Don't Know (Rock Song)

IX. Gospel Sermon "God Said")

***

Bernstein was invited in 1973 to the Charles Eliot Norton Chair as Professor of Poetry at his alma mater, Harvard University, to deliver a series of six lectures on music. Borrowing the title from a Charles Ives work, he called the series The Unanswered Question, a set of interdisciplinary lectures in which he borrows terminology from contemporary linguistics to analyze and compare musical construction to language.

***

Dybbuk (ballet), 1974

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, 1976

***

In 1976, the entire series of videotaped Norton lectures was telecast on PBS. The lectures survive both in book and DVD form today. Chomsky wrote in 2007 on the Znet forums about the linguistic aspects of the lecture: "I spent some time with Bernstein during the preparation and performance of the lectures. My feeling was that he was on to something, but I couldn't really judge how significant it was."

Bernstein's later recordings (1976 onwards) were mostly made for Deutsche Grammophon, though he would occasionally return to Columbia Masterworks. Notable exceptions include recordings of Berlioz' Symphonie Fantastique (1976) for EMI and Wagner's Tristan und Isolde (1981) for Philips Records, a label joint with Deutsche Grammophon as PolyGram at that time.

***

Songfest: A Cycle of American Poems for Six Singers and Orchestra, 1977

Slava!: A Political Overture for Orchestra, 1977

***

In 1978, the Otto Schenk Fidelio, with Bernstein still conducting, but featuring a different cast, was filmed by Unitel. Like the program, Bernstein on Beethoven, it also was shown on A&E after his death and subsequently issued on VHS. Although the video has since long been out-of-print, it was released for the first time on DVD by Deutsche Grammophon in late 2006.

Bernstein conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for the first and only time, in two charity concerts, in 1979. The performance, of Mahler's Symphony No. 9, was broadcast on radio, and posthumously released on CD.

***

The Madwoman of Central Park West (songs), 1979

Divertimento for Orchestra, 1980

***

Bernstein received the Kennedy Center Honors award in 1980.

On PBS in the 1980's, he was the conductor and commentator for a special series on Beethoven's music, which featured the Vienna Philharmonic playing all nine Beethoven symphonies, several of his overtures, one of the string quartets arranged for the full string section of the Vienna Philharmonic, and the Missa Solemnis. Actor Maximilian Schell was also featured on the program, reading from Beethoven's letters.

***

Halil, nocturne for Solo Flute, Piccolo, Alto Flute, Percussion, Harp and Strings, 1981

A Quiet Place (opera in two acts), 1983

***

In 1985, he conducted a complete recording of his score for West Side Story for the first and only time, and a TV documentary of the sessions was additionally issued. The recording features Kiri te Kanawa, Jose Carreras, and Tatiana Troyanos in the leading roles, and was a national bestseller.

Bernstein conducted his sequel to Trouble in Tahiti, A Quiet Place, in 1986 at the Vienna State Opera.

***

Jubille Games, 1986, revised as Concerto for Orchestra, 1989

The Race to Urga (musical), 1987

Arias and Barcarolles for Mezzo-Soprano, Baritone and Piano four-hands, 1988

Dance Suite, 1988

Missa Brevis for Mixed Chorus and Countertenor Solo, with Percussion, 1988

***

Bernstein's final farewell to the State Opera happened accidentally in 1989: Following a performance of Modest Mussorgsky's Khovanchina he unexpectedly entered the stage and embraced conductor Claudio Abbado in front of a stunned, but cheering audience.

That same year, Bernstein conducted and recorded Candide, released posthumously on CD in 1991. It starred Jerry Hadley, June Anderson, Adolph Green, and Christa Ludwig in the leading roles. The Candide recording also included previously discarded numbers from the show. The Candide recording was made live, in a concert eventually telecast posthumously.

On Christmas Day, 25 December 1989, Bernstein conducted the Beethoven Symphony No. 9 in East Berlin's Schauspielhaus (Playhouse) as part of a celebration of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The concert was broadcast live in more than 20 countries to an estimated audience of 100 million people. For the occasion, Bernstein reworded Friedrich Schiller's text of the Ode to Joy, substituting the word "Freiheit" (freedom) for "Freude" (joy).

Bernstein, in the introduction to the program, said that they had "taken the liberty" of doing this because of a "most likely phony" story, apparently believed in some quarters, that Schiller wrote an Ode to Freedom that is now presumed lost. Bernstein's comment was, 'I'm sure that Beethoven would have given us his blessing."

Bernstein conducted his final performance at Tanglewood on August 19, 1990, with the Boston Symphony playing Benjamin Britten's Four Sea Interludes and Beethoven's Symphony No. 7.

He suffered a coughing fit in the middle of the Beethoven performance which almost caused the concert to break down. The concert was later issued on CD by Deutsche Grammophon.

He died of pneumonia and a pleural tumor just five days after retiring. A longtime heavy smoker, he had battled emphysema from his mid-20s. On the day of his funeral procession through the streets of Manhattan, construction workers removed their hats and waved and yelled "Goodbye Lenny."

Bernstein is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, New York, NY.

[8919 Nat King Cole / 8918 Bernstein / 8917 Gillespie]